Effectively using slots in Jetpack Compose

Jetpack Compose is great for developing UIs for Android (and more!). Declarative UI comes with its own set of problems and quirks though, and that in turn opens the door for idioms and patterns specific to this declarative nature.

One such problem with Jetpack Compose is having to pass parameters through from a Composable down to its children (Note: this problem is not specific to Compose, it is also seen with SwiftUI, Flutter and ReactNative). In this post, we’ll look at how to use Composable lambdas (also called “slots”) to improve the situation.

Example

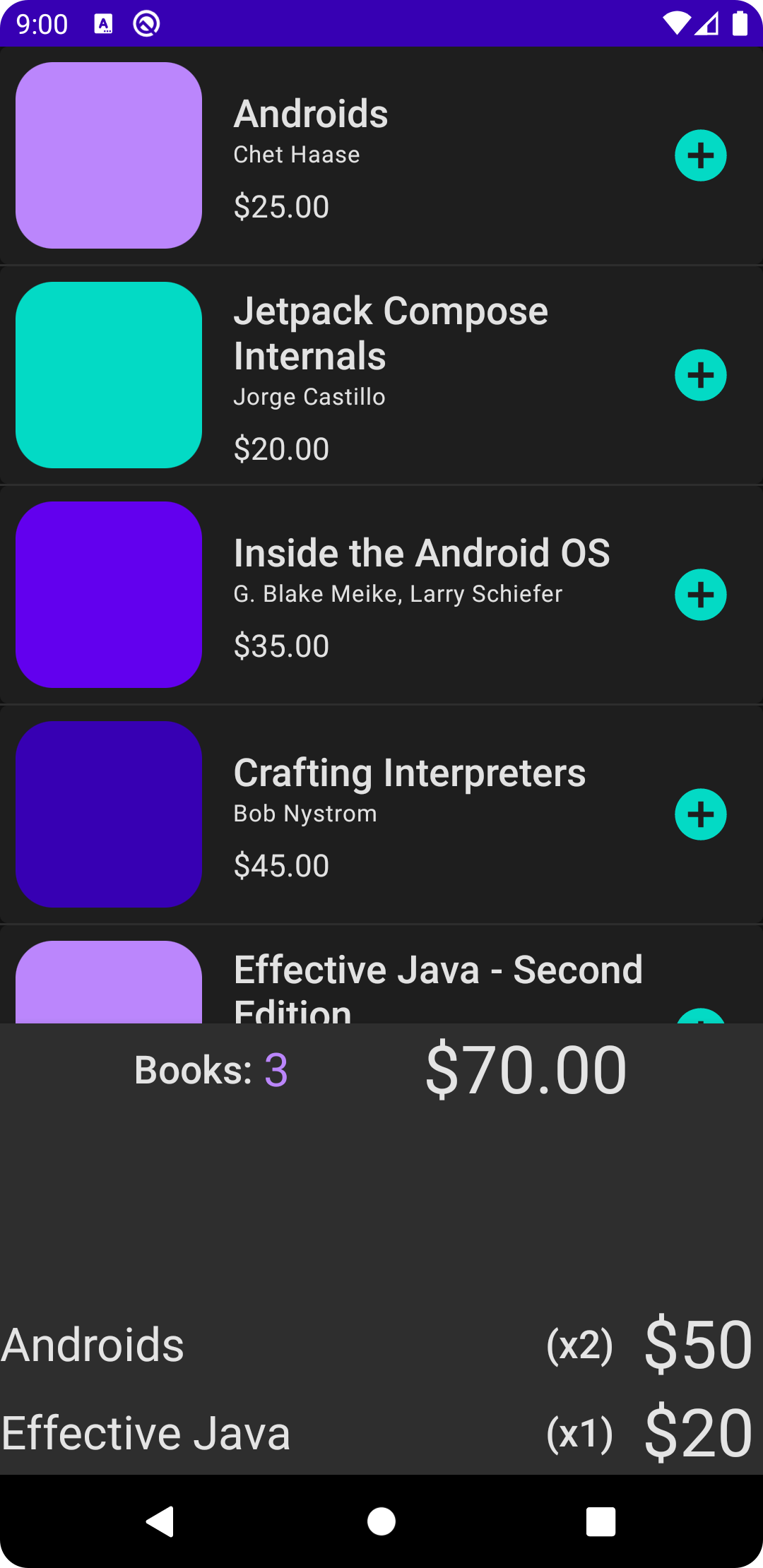

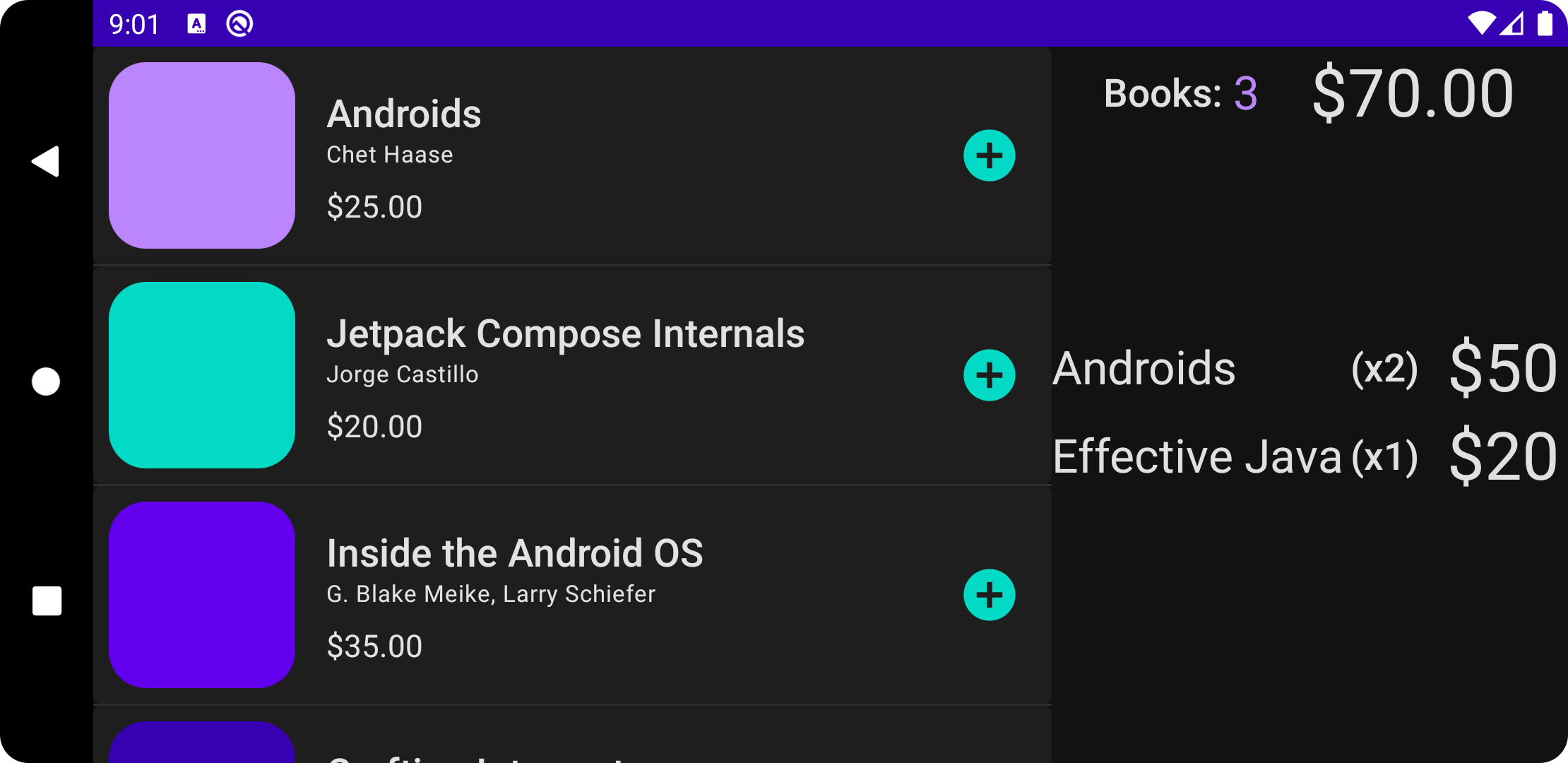

Let’s look at an example: A screen showing a list of books to buy and a shopping cart. On narrow screens, the list of books takes up the entire width and the shopping cart is placed in a bottom sheet. On wide screens the list of books takes up the first 65% of the screen width while the shopping cart takes up the rest.

Here are a couple of screenshots. It does not look pretty, but it serves the purpose of this post.

Implementation

Here is how one might implement it (GitHub source):

@Composablefun MainScreen(mainScreenModel: MainScreenModel, isWideScreen: Boolean = false) { if (isWideScreen) { Row(Modifier.fillMaxHeight()) { Box(Modifier.weight(0.65f)) { BookList( books = mainScreenModel.books, onBookAdded = {} ) } Box(Modifier.weight(0.35f)) { ShoppingCart(shoppingCartModel = mainScreenModel.shoppingCartModel) } } } else { BottomSheetScaffold( sheetContent = { ShoppingCart(shoppingCartModel = mainScreenModel.shoppingCartModel) } ) { BookList(books = mainScreenModel.books, onBookAdded = {}) } }}The MainScreen composable receives the the MainScreenModel as a parameter, and it passes pieces of this data to child composables:

- The

booksproperty, which is aList<BookModel>, is passed to theBookListcomposable - The

shoppingCartModelproperty is passed to theShoppingCartcomposable.

The call site is straightforward:

MainScreen(mainScreenModel = sampleMainScreenModel)In this simple example, it doesn’t look all that bad. However, it starts getting tedious when your MainScreen needs to pass that the same model (and callback lambdas) further down the tree.

Slots to the rescue

If a Composable accepts another Composable as a parameter, then that parameter is called a slot. Many core composables are designed this way:

- All the basic layouts like

Row,ColumnandBoxaccept acontentparameter that is a Composable lambda. - Components like

ButtonandCarddo the same. - More advanced components like Scaffolds accept multiple composable lambdas for different sections of the scaffold. For example,

BottomSheetScaffoldhas five(!!) slots for thesheetContent,drawerContent,snackbarHost,floatingActionButtonand thecontentitself.

Let’s change our MainScreen composable to accept slots. Here’s the signature:

@Composablefun MainScreen( shoppingCartContent: @Composable () -> Unit, booksContent: @Composable () -> Unit, isWideScreen: Boolean = false)What we’ve done here is to accept two Composables as parameters, one each for the shopping cart section and the books list section. Now the implementation changes to this:

@Composablefun MainScreen( shoppingCartContent: @Composable () -> Unit, booksContent: @Composable () -> Unit, isWideScreen: Boolean = false) { if (isWideScreen) { Row(Modifier.fillMaxHeight()) { Box(Modifier.weight(0.65f)) { booksContent() } Box(Modifier.weight(0.35f)) { shoppingCartContent() } } } else { BottomSheetScaffold(sheetContent = { shoppingCartContent() }) { booksContent() } }}Note that now the MainScreen composable does not pass along any data parameters at all. It now has the focused responsibility of dealing with the layout rather than also having to forward parameters. It only receives parameters that it uses directly (isWideScreen). The slots it receives are opaque to it and it does not need to know what parameters they need or what callback lambdas they offer.

Also note that if you change the signature of either BookList or ShoppingCart (add, remove, reorder parameters), MainScreen does not need to change at all.

Here’s what the call site looks like:

MainScreen( shoppingCartContent = { ShoppingCart(shoppingCartModel = sampleMainScreenModel.shoppingCartModel) }, booksContent = { BookList( books = sampleMainScreenModel.books, onBookAdded = {} ) }, isWideScreen = true)You’ll notice that we pushed considerable responsibility to the call site. That brings us to the next topic:

When to use slots?

This pattern of using composable slots makes some trade-offs. So it is not the right choice for all situations. In particular, it means the caller of this composable

- Is exposed to more knowledge of the inner workings of the composable. In this case, the caller previously did not know that

MainScreenis split into two high-level sections but now it does. - Is required to split the data itself rather than having

MainScreendo this job

Because of these factors, slots work best when in the following situations:

- You want to hide complexity from the “in-between” levels of the tree of Composable nodes. This means that you have some intermediate composables that you don’t want to be burdened with passing data around

- You are creating reusable generic layouts or components like Row or Scaffold

- Near the top of your Composable tree. For example you could have a top-level Composable observe state changes from a ViewModel and instead of dumping the entire composite state object to a Composable, it could partition the state into several sections and pass them as one composable per section.

It is not a good idea to use this technique at all levels though. In particular, when you are near the leaves of your tree of Composable nodes, it is more convenient to pass data parameters. For example, the ShoppingCart composable used in this demo does not use slots.

Credits

Thanks Adam Powell for explaining the idea of slots and for reviewing this article.